The importance of feeling seen

Reflections on representation and embracing my South Asian identity

May is APIA (Asian and Pacific Islander American) Heritage Month in the U.S. I can’t speak to the collective APIA experience, primarily because there isn’t one. To echo what many have said, this group is not a monolith. Each subcommunity, while sharing commonalities in certain areas, has its own nuances, historical challenges, and contemporary struggles.

Even within the South Asian American population — those of us with roots stemming from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, the Maldives, Afghanistan — there are myriad languages, cultures, socioeconomic factors, and religions to consider.

We all have our own story to tell. The following essay discusses the path to accepting my South Asian identity as a first-generation Indian American.

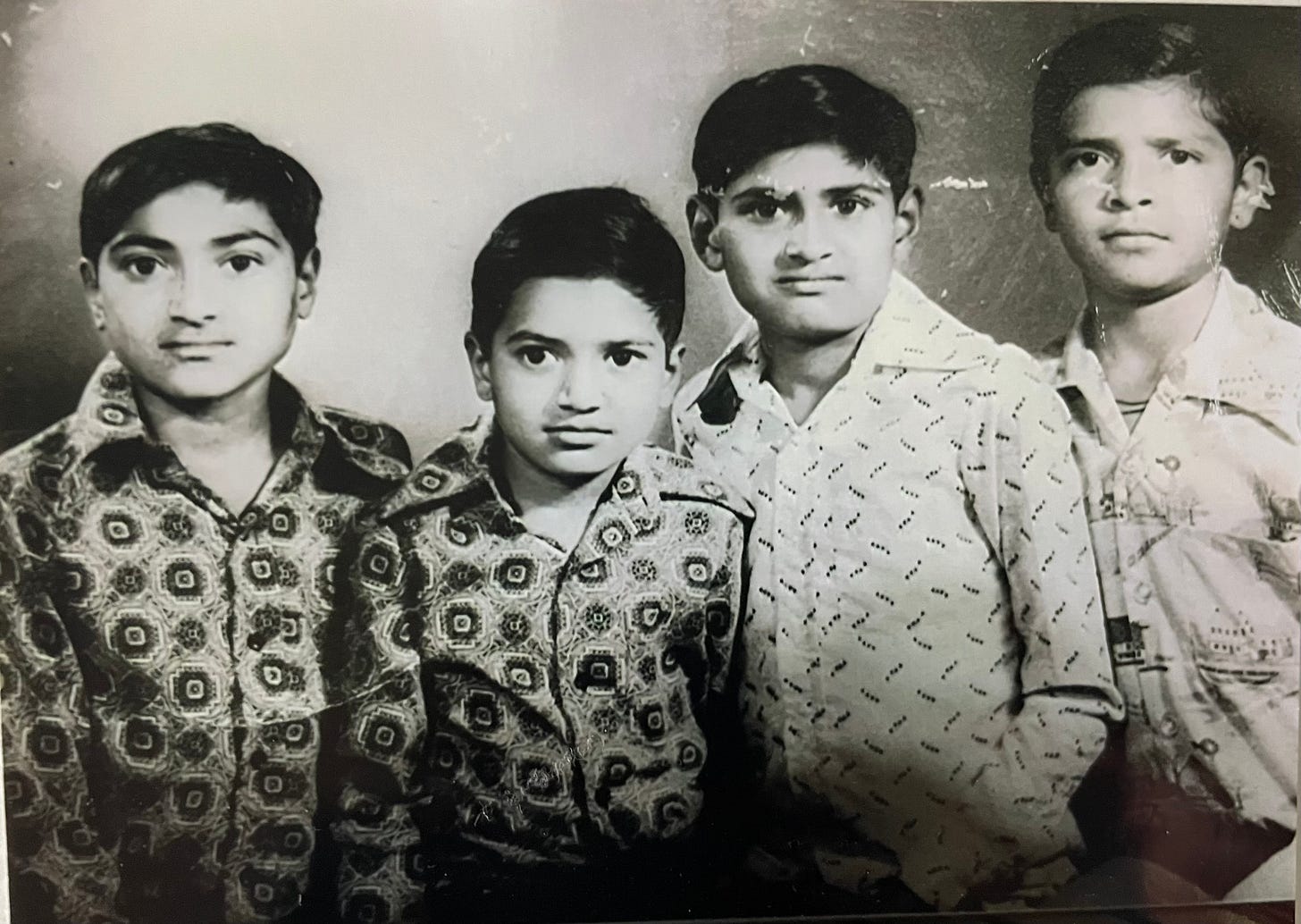

Though I was born in the U.S., my grandparents steadfastly steeped me in our Gujarati culture. I spoke the language at home, ate the shaaks and kadhi bhaat my grandma made, and attended bhajans with the family. We entertained a constant stream of guests — relatives, family friends, and those somewhere in between. Hindi-language soap operas or news broadcasts played in our living room, nearly every hour of the day.

In hindsight, I see the richness of such an upbringing. The cultural traditions and tight-knit community cultivated a deep sense of comfort during those early years.

Once I entered elementary school, however, this foundation began to falter. I grew up in a relatively small, mostly white city in California’s Central Valley, as one of the only South Asian kids in school. This was also at the onset of the millennium. The race conversation hadn’t entered the mainstream discourse in the way it unfolds today. When racial inequality did come up, it was poised as a problem of the past — an issue limited to the pages of history books — not an ongoing occurrence.

Yet my experiences told a different story.

I witnessed the way other kids taunted the Punjabi Sikh boy in my grade for his turban. One day, while playing hopscotch with my friend Amanda during recess, her older sister pulled her aside and warned her to stop hanging out with me because of my brown skin. I noticed the way my dad began to over-explain himself — assuring people he had no ill intentions — in the post-9/11 period.

Each of these instances — and myriad others to follow — made one thing clear. Being a brown person inherently meant not being enough. The pride, awe, and belongingness I’d developed in my first few years gave way to shame, humiliation, and a deep desire to hide. To not be seen as different.

And so, I embarked upon a slow but steady suppression around the Indian side of my identity. Though I couldn’t change my physical complexion (thankfully, my family didn’t use skin whitening creams), I could change the way I behaved.

I had my mom pack me cheese sandwiches for lunch (which went uneaten), even though I craved papdi no lot or bhinda nu shaak and rotli. I never spoke of my Bollywood dance performances or our annual Navrati celebrations — both of which brought me immense joy.

I also learned to compartmentalize my identities: the Indian version of myself (at home) and the American version (at school). Like a switch, I flipped one off before entering the other, careful to not let too much of the Indian version spill into the American one. Despite the seamlessness of it externally, I was slowly caving in on the inside.

When I entered college, I reveled in the ability to geographically distance myself from my Gujarati culture. Shedding the “good Indian girl” image I’d grown up with, I came to embody a new persona entirely. I joined a sorority and partied incessantly. I stopped observing cultural and religious holidays. I took the fetishization of my brownness as a sign of my inherent worthiness, oblivious to its racist undertones.

The approval I’d sought since those elementary school years remained elusive.

A Lack of On-Screen South Asian Role Models

Growing up, we had little guidance on how to take pride in our roots as diaspora kids in the western world. We saw the way our immigrant elders were treated with disdain. Their close ties to their homelands (through the clothes they wore, languages they spoke, foods they ate) resulted in stares, whispers, and all sorts of slurs. We wanted to assimilate so we didn’t face the same fate.

South Asian representation in the media was sparse. Whenever South Asian characters did receive screen time, they were used mainly as humorous asides that reinforced pre-existing stereotypes (the most common examples being Raj from The Big Bang Theory and Apu from The Simpsons). Such “representation” perpetuated the shame that so many of us within the diaspora felt.

Furthermore, this 2022 report by The Representation Project found that South Asian female characters, in the meager screen time they received, also fell in line with existing stereotypes. They were commonly portrayed as the “Exotic Love Interest,” the “Innocent Love Interest,” or the “Medical Professional.”

As this blog post by Seven Six Agency points out, such misrepresentation “results in the ‘othering’ of South Asians,” leading to “racial discrimination and lack of opportunities that members of our communities receive, particularly across the US, UK, Europe and Australia (read: white majority countries).”

And then there were missed opportunities, which left so many of us confused and wondering, “Why didn’t more come of this?”

The most notable case: Bend It Like Beckham, Gurinder Chadha’s 2002 film starring Parminder Nagra and Kiera Kightley. I remember watching that film and feeling so seen by the main character, Jess. She fell short of meeting the expectations of both cultures — English and Indian — within which she lived. Jess’ ability to chart her own path in life and speak up for herself inspired me and allowed me to dream a little bigger. (As this Teen Vogue piece points out, it was disappointing to not see Nagra’s career take off to the extent Knightley’s did.)

The TV shows I watched and books I read as a kid lacked this deeper cultural relatability. They didn’t come close to addressing the same pain points. To directly speaking to those shameful parts and saying, “Hey, there is space for you in this world.”

So many of us, as far back as we could remember, yearned for more. More than a quick two-line appearance from a South Asian character on screen, or a minor character in a novel, later asking ourselves, “Wait… what’s her story?”

A Shift in the Landscape

The 2020s have brought an increase in South Asian representation, alongside a large-scale movement for more inclusion overall.

When I first watched Never Have I Ever at the start of the pandemic, I felt a mix of relief and excitement. Yes, the show has its cringey aspects, but it gave so many of us what we’d been waiting for. Maitreyi Ramkrishnan’s character, Devi, is a hot mess, always landing in some sort of trouble and rebelling against her mom’s rules — a refreshing antidote to the has-her-shit-togetherness we’d been socialized to aspire to.

Like Jess from Bend It Like Beckham, Devi normalized the importance of f***ing up a few times in order to figure out life.

I was also moved by Ambika Mod’s character, Emma Morley, in Netflix’s adaptation of One Day. Something about Mod’s performance, and the show overall, showed me a different side of representation, one I hadn’t previously thought much about.

As Aysha Qamar writes in this Brown Girl Magazine article, “Mod’s role in ‘One Day’ reminds us that South Asians and South Asian identity are not defined by their culture and the widespread stereotypes associated with it and hence, do not need to play roles that put them in boxes. Real representation is not being tokenized for what we identify as but being featured on screen just as anyone else.”

The representation shift isn’t just limited to television. We’re also seeing more South Asians on the big screen, the stage, the podium, and the page. And in these representations, we’re simultaneously grasping how our ethnicities often intersect with other identities (gender, sexuality, disability status, etc.).

Dev Patel’s Monkey Man received praise for being one of the first mainstream films to feature hijra (transgender) representation. Performance artist and writer Alok Vaid-Menon has done groundbreaking work around dismantling the gender binary.

Raveena Aurora and Ali Sethi are two openly queer musicians who’ve performed at Coachella, one of the world’s biggest festivals, alongside other South Asians.

In the realm of chronic illness and disability, Nitika Chopra has created a global community and nonprofit to support those living with chronic conditions.

Books by South Asian authors are taking up more shelf space, and a lot of us are realizing the importance of reading stories from fellow diaspora members. I recently enjoyed Prachi Gupta’s memoir, They Called Us Exceptional. It criticizes the model minority myth and discusses the mental toll of trying to uphold American and Indian cultural expectations — and never feeling like enough within either space.

It’s been refreshing to see more South Asian representation in these areas. Still, I come back to a single question: why has it been such a slow, arduous process? Many of us millennials and Gen Xers may also juggle dual feelings of jealousy (towards younger generations) and optimism with this increase in representation.

writes about this conundrum wonderfully in her Substack essay.Why Does Representation Matter?

I’m realizing that representation is constantly evolving, both as I conceptualize it in my own mind and as it plays out in the world.

Representation doesn’t mean filling quotas, or giving someone a few seconds of screen time to check a figurative box. Representation is about capturing the nuances and complexities of a marginalized group. It’s about pushing back against stereotypes and giving people who’ve been left out of writing rooms and decision-making processes the space to tell their own stories.

Representation urges us to ask the difficult, traditionally avoided questions. And when done right, it gives us permission to reclaim and fully lean into those parts of ourselves we’ve tucked away.

When we see ourselves in characters or public figures, we begin to crack away at the walls of shame that have kept us — and the generations before us — from embracing who we are. Representation also makes the seemingly impossible feel possible. When we see someone else do what we always thought we “shouldn’t” do, we realize we’re capable, too.

As this Psychology Today article points out, “Representation should never be the final goal; instead, it should merely be one step toward equity. Being the ‘first’ at anything is pointless if there aren’t efforts to address the systemic obstacles that prevent people from certain groups from succeeding in the first place.”

Reclaiming My South Asian Roots

It’s been an ongoing journey spanning over two decades, but I can finally say that I’m proud to be South Asian. While media representation has played a major role in helping me honor this part of my identity, it’s not the only factor.

I’ve had the privilege of going to therapy. These sessions have given me the additional context (and language) to understand harmful beliefs and behaviors stemming from intergenerational trauma. Therapy has also taught me how to be more compassionate towards myself; to slowly detach from the people-pleasing and perfectionistic patterns I’d picked up in childhood.

I visited India and Nepal during my post-grad gap year, as well. During this time, I met women who were strong female leads in their own lives. They took pride in their South Asian roots but simultaneously challenged marital, religious, and career-related expectations.

Through each of these experiences, I’ve learned that my Indian and American identities can coexist. That all of my identities can coexist. Life opens up in new ways when I embrace these sides of myself, rather than trying to escape them.

I appreciate many of the customs, values, and practices I was raised with, and want to preserve the richness of these traditions. However, there are still stigmas and detrimental narratives to dismantle within our own community. The work is ongoing — a lifelong endeavor — but few things in life fill me with greater purpose.

When we feel seen, we learn to own — and share — our stories. These stories remind us that there’s no need to prove or minimize ourselves for others’ comfort. That we deserve to show up as we are. And, ultimately, that we matter.

🎨 Creativity Corner

Essay: “Therapy Helped Me Find Pride in My South Asian Heritage” (I had the honor of discussing my therapy journey — and how it’s helped me connect with my culture — in this POPSUGAR piece)

Poem: “Journey Home” by Rabindranath Tagore (a poem that I continually come back to; I especially love the line “… one has to wander through all the outer worlds to reach the innermost shrine at the end.”)

Instagram page: @browngirlbookshelf (Mishika and Sri have always done a wonderful job of spotlighting books and other forms of written work by South Asian authors)

Excellent work, Brina. I am so glad I read this. "why has it been such a slow, arduous process?" I would suggest that racists are filled with jealousy, insecurity, fear, and ignorance. I'm so sorry you had to endure such behavior, but thrilled at the effort your putting into your awesome self. There are many, like myself, who appreciate and look up to different cultures that have enriched this planet for thousands of years vs. America. (1796)